Windows of Consumption

A window defines both what it admits and what it excludes. Light floods through its frame not because the sun changes, but because the aperture allows it. In fasting, our “windows of consumption” are not about how much food passes through the body, but when. By narrowing that frame, we do not diminish abundance—we concentrate it.

For me, this practice has become second nature. I often fast 18 hours a day, sometimes stretching to 22 or 23. My window of consumption opens in the late afternoon—14:00, 15:00, sometimes 19:00—and within that compressed span the day’s nourishment is taken in. At nearly 70 years old, I attribute much of my vitality, lean figure, and clarity of mind to this discipline. But what is happening physiologically when we shrink the window of eating, even if the total calories remain unchanged?

Science is beginning to answer. Researchers call it time-restricted eating (TRE), a practice that sits at the intersection of nutrition and chronobiology. Unlike calorie restriction, which simply reduces intake, TRE synchronizes eating with the body’s circadian rhythm. Human metabolism is not a flat line; it follows the rise and fall of light. Hormones, enzymes, and cellular repair all operate on clocks. To eat against that rhythm is to confuse the system; to eat with it is to amplify efficiency.

Consider insulin, the hormone that escorts glucose into cells. A controlled study led by Courtney Peterson and Satchidananda Panda found that early time-restricted feeding—an eating window that closed by mid-afternoon—reduced fasting insulin by ~26 mU/L and improved insulin sensitivity by over 30%, independent of weight loss. Even when calories were identical, timing changed how the body handled them. This means the same meal at 09:00 and 21:00 does not land the same way in the bloodstream.

In people with metabolic syndrome, a 10-hour window improved not only weight and abdominal fat, but also blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose regulation. In type 2 diabetics, a 12-week trial of TRE lowered blood glucose, improved insulin sensitivity, and induced modest weight loss—again, without requiring calorie reduction or added exercise. The act of eating within rhythm became its own form of medicine.

Meta-analyses reinforce these findings. A synthesis of 20 studies showed that TRE reduced body weight by ~1.4 kg, fat mass by ~0.75 kg, and waist circumference by ~1.87 cm—even when total calories were controlled. Early windows (aligned with daylight) proved most effective. Notably, benefits extended beyond body composition: markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular strain were improved.

The mechanism lies deeper than digestion. By lengthening the daily fast, we activate autophagy—cells clearing debris, proteins folding correctly, mitochondria repairing themselves. We allow insulin to rest, cortisol to follow its natural morning peak, and melatonin to anchor night. TRE is less about subtraction than about allowing the body’s symphony to play on time.

Yet science also issues cautions. A Johns Hopkins randomized trial showed that time restriction, when calories were tightly controlled, did not outperform standard calorie reduction for weight loss. The message is not that windows don’t matter, but that discipline in timing is not magic. It is rhythm—most powerful when paired with restraint, sleep hygiene, and movement.

Philosophically, this makes sense. A window is not a feast; it is a frame. It is the difference between light scattered and light focused, between noise and music. Fasting narrows the span, not to deny abundance, but to direct it. Each pang is a reminder: freedom often lives inside form.

Across cultures, this truth has echoed. From Islamic Ramadan to the Vedic traditions of Ekadashi, from Stoic discipline to monastic hours, windows of consumption have always existed. They were not counted in calories but in hours of prayer, work, and rest. In the modern age, science now speaks what wisdom long intuited: to live well, we must not only ask what we eat, but when.

So the question becomes: What is your window of consumption? Where do you frame the day so that nourishment, clarity, and presence all align? Mine is a pane of glass, narrow and deliberate, through which the rest of life feels sharper, leaner, more luminous.

Wisdom’s Lens

Satchidananda Panda: “The benefits of fasting may come less from how much we eat and more from when we eat.”

🔎 Panda reframes fasting as timing, not tally—reminding us that rhythm itself can be the medicine.

Affirmation

I honor the rhythm of my body by narrowing the window through which I feed it.

🪶 Poem

Windows of Consumption

The frame is narrow,

but the view expands.

Light gathered,

time contained.

Hunger waits,

not as absence,

but as aperture—

a window that steadies the soul.

— R.M. Sydnor

POETRY ANALYSIS

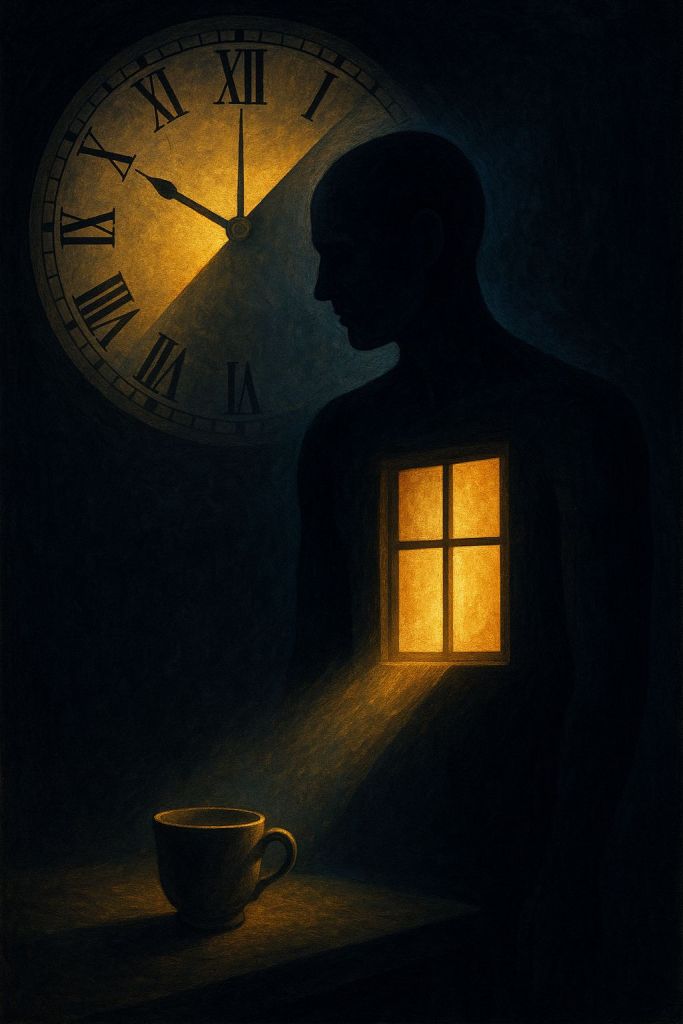

ARTWORK DETAILED DESCRIPTION

Closing Thought

The narrower the window, the wider the freedom.

Annotated References

1. Sutton EF, Beyl R, Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even Without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metabolism. 2018.

This landmark study tested a 6-hour eating window (8am–2pm) in overweight men with prediabetes. Despite identical calorie intake, participants improved insulin sensitivity by 31%, reduced blood pressure, and lowered oxidative stress—all without losing weight. Timing alone improved metabolic health.

2. Wilkinson MJ, Manoogian ENC, Zadourian A, et al. Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metabolism. 2020.

In this 12-week trial, adults with metabolic syndrome shifted to a 10-hour eating window. Participants lost weight, reduced waist circumference, lowered blood pressure, and improved cholesterol markers—demonstrating TRE’s impact in high-risk populations.

3. Jamshed H, et al. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves 24-Hour Glucose Levels and Fasting Insulin in Men with Prediabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019.

By compressing eating into an early window, men with prediabetes saw significant drops in fasting insulin and improved glucose control. The findings show that early alignment with circadian rhythms provides an edge over late-night eating.

4. Liu K, et al. Effect of Time-Restricted Eating Combined with Caloric Restriction on Weight Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2023.

Reviewing 20 studies, this analysis found that TRE consistently reduced weight, fat mass, and waist circumference, even when calories were matched. It highlighted that early TRE (daylight aligned) yielded the strongest effects.

5. Chow LS, et al. Time-Restricted Eating Effects on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Adults with Obesity. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2022.

This large randomized controlled trial tempered enthusiasm, showing that TRE did not outperform calorie restriction for weight loss when calories were strictly controlled. The study cautions that TRE is not a silver bullet but part of a broader lifestyle strategy.

6. Cienfuegos S, et al. Effects of 4- and 6-Hour Time-Restricted Feeding on Weight and Metabolic Disease Risk Factors. Nutrition and Healthy Aging. 2020.

Tested ultra-short eating windows (4–6 hours). Results showed reduced calorie intake, weight loss, and improvements in insulin resistance. Suggests that extreme narrowing of the window amplifies benefits, but sustainability remains a question.

7. Panda S. The Circadian Code: Lose Weight, Supercharge Your Energy, and Transform Your Health from Morning to Midnight. Rodale, 2018.

Panda’s book synthesizes years of circadian biology research, arguing that aligning eating, sleeping, and activity with circadian rhythms restores metabolic health. It popularizes TRE with scientific grounding and practical application.