Act I: The Preparation

By late afternoon, sycamores along the block let go of their freckled leaves one by one, slow as careful handwriting. Air cooled after a day that baked the sidewalks pale. Plastic skeletons rattled on porches, not from menace but from the small draft that moves through neighborhoods before dusk. Children rehearsed trick-or-treat voices on stairwells. Someone tested a fog machine; eucalyptus swallowed the hiss.

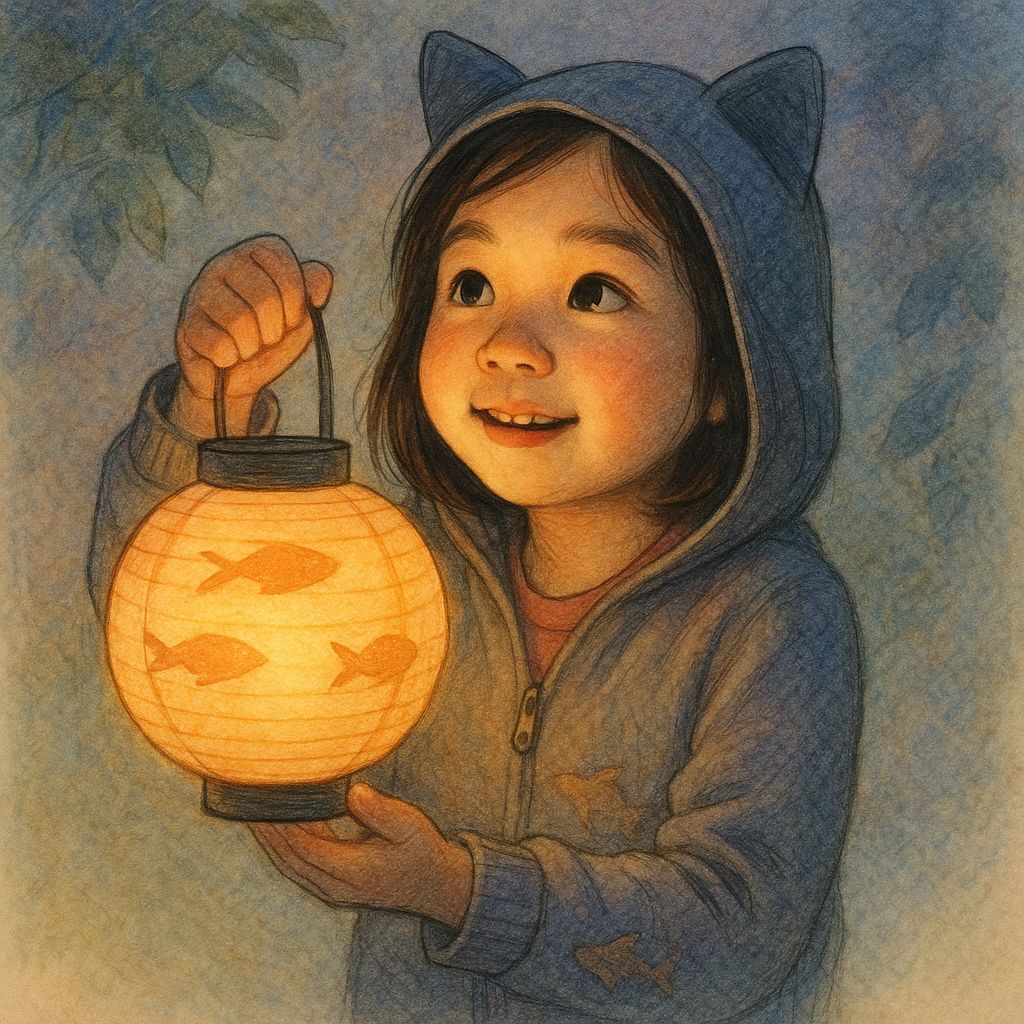

Mei Lin laid a length of orange ribbon on the kitchen table and checked the knot-ends for fray. June’s lantern waited beside a cereal bowl, a hexagon of cardstock stitched with thin wire, windows cut in fish-shapes that swam when the light shifted. June had painted each fish like a comet with a bright eye and a tail that refused to tire. The paint caught whatever light the room offered and made more of it.

You didn’t need to make it so beautiful, Mei Lin said. People hand you candy even if you carry a pillowcase.

Handmade looks happier, June answered, chin up inside a gray hoodie with small cat-ears sewn on. She wiggled a front tooth that had begun to sway; the tooth bobbed like a buoy in a harbor no one could see.

The ribbon threaded the wire handle; Mei Lin pulled through and tied a square knot. The knot held. Good. Things should hold. She turned the lantern once, testing the balance. Solid. A small light would sit inside and breathe like a careful animal.

On the counter, a tray of dumplings rested beneath a dish towel. She had folded them at noon between affidavits, thumbs moving as if they remembered a tune without the sheet music. She meant to pan-fry them before the rounds, eat three, maybe four, and leave the rest for later. Then the office called with a missing signature and the afternoon ran like a dog that slips a leash.

Her gray cardigan snagged on the drawer pull again. That thread kept catching. She clipped the loose end with kitchen scissors and placed the scissors flat, as if metal also needed mercy.

Across the street, Mr. Delgado had planted folding chairs in his driveway like beach flags. A thermos steamed beside a bowl of candy large enough to beach a canoe. He wore his Dodgers cap low, as if October required ritual. Every year he name-checked the cost of chocolate with theatrical outrage and then doubled the quantity anyway. Every year he pretended to scold kids for greedy handfuls and then told them to take one more for the long walk home.

Her phone hummed on the table. Auntie Rui.

You picked a lucky evening, Auntie said, voice rich from choir practice and old opera days. Hungry month ended, but hunger lingers. Keep an orange on your table. Keep water, too. When you pass a crossroad, don’t turn if the wind calls your name.

We’ll stick to Sycamore and back, Mei Lin said, the practical tone she wore like good shoes. No crossroads. No detours. A little candy. Bed before nine.

Who made the lantern?

June did.

Then listen to me: when you light a lantern, you ask the ones who love you to walk a while. That never harms. That comforts.

Auntie, I have work. We have rules here—cross at corners, look twice, no running. That’s enough magic for one night.

Rules keep the living safe, Auntie said. Ritual keeps the living beloved. Put both on the table and eat.

Mei Lin smiled despite herself. She loved Auntie Rui, loved that voice, loved the warm insistence. She also loved rent paid on time and forms with correct middle initials. She poured two glasses of water anyway and set an orange near the sink. Habit can kneel without drama; kneeling still counts.

June hopped down from the chair. Can we go? My lantern needs night.

You need night. The lantern needs a candle, Mei Lin said, but she softened the tease with a kiss to June’s hoodie ear. She tucked tissues and a flashlight into her tote. She slipped the spare charger beside the bandages and the tiny sewing kit, the kit that saved the day more often than the bandages.

They stepped outside. The courtyard palms waved like friendly stage-hands. Someone on the second floor had taped a paper bat to the railing; the bat pivoted with every draft, a good dancer on a simple hinge. Down on the sidewalk, leaves dragged secrets along concrete. A porch two doors down wore a web spun of white string, neat enough to please a geometry teacher. Across the street, a pirate argued with an astronaut about jurisdiction.

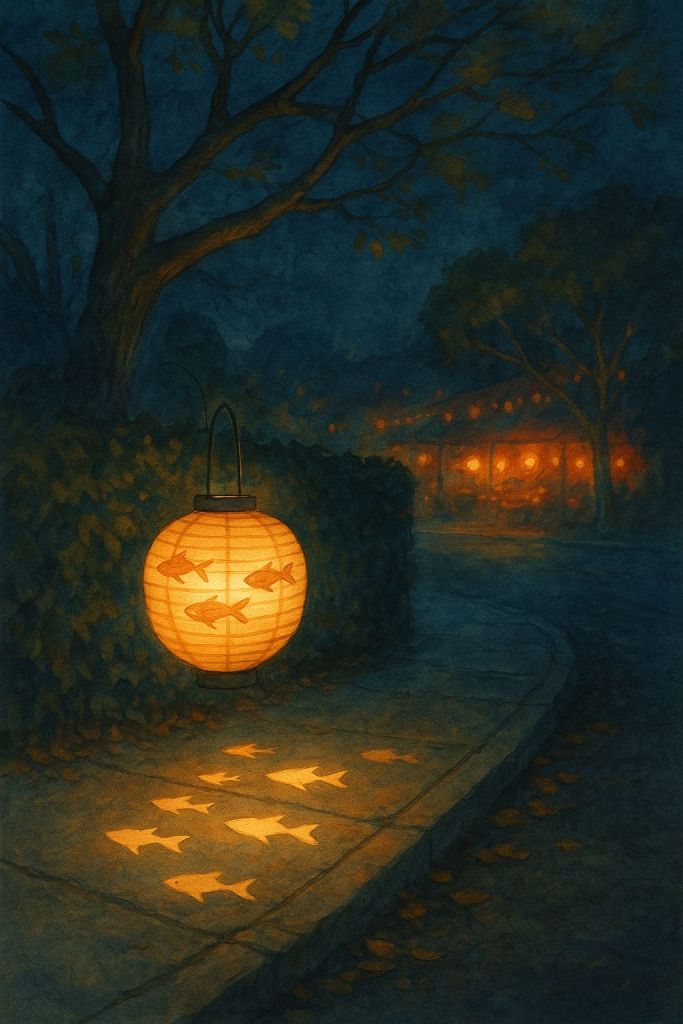

Mei Lin knelt and set a tea light inside the lantern. Wick met flame; flame trembled and took its place. The fish windows filled with copper and gold. June lifted the handle, reverent, and the light changed her face—less cat, more comet.

Pretty, Mr. Delgado called. Start on this side, then cross at me, okay? Less street, more chocolate. And Mei, take one for energy. I’ll pretend I didn’t see.

I’ll trade you a dumpling later, she said.

Trade accepted. The Dodgers won, so I baked, he answered, and he tipped the thermos like a toast.

They walked. First porch: a witch with a smudge of flour on her cheek passed out gummy worms. Second porch: a vampire with a kind mouth offered raisins from the little red box with a forever-smiling girl on it. June said thank you every time, not like a parrot but like a person who understands the precise weight of small gifts. Mei Lin watched curbs, dogs, and drivers—always the drivers—who stared at phones and missed the way children tilt toward joy.

At the fourth lawn, a slip of wind threaded the lantern. The flame bent, not wildly, not in panic, more like a bow. The fish swam toward the hedge as if a river had switched direction.

June whispered, I think the lantern wants to go that way.

Lanterns don’t want. People want, Mei Lin said. We choose the bowls with chocolate, remember? That strategy pays.

Another draft. Sycamore leaves rustled like paper money in a lucky envelope. The flame leaned deeper toward a thin break in the hedge. Mei Lin tightened her grip on the flashlight. Auntie’s words nudged her ear: If it bends, someone breathes with you.

A back door probably opened. A space heater probably stirred air. Maybe memory. Maybe poor insulation. She squeezed June’s shoulder. Mr. Delgado next, she said. We’ll cross to him and circle back.

Can we peek through the gap? June asked. I saw it this morning when we walked to school. It looks like a secret.

No hedge tonight, Mei Lin said. We keep the loop simple.

June drifted toward the gap anyway, drawn by the kind of logic children carry in their pockets: gaps exist because someone should pass through. The lantern wrote a copper line across leaves. The flame leaned close to paper, then corrected itself, as if a whisper steadied it.

Stay with me, Mei Lin said.

I’m right here, June answered, feet already crunching the first dry leaf inside the hedge’s sleeve.

The gap opened onto a garden that didn’t match any yard on the street. Narrow paths crossed like old X’s on a map. Stepping stones wore chipped paint—numbers once, perhaps, now down to ghost colors. A clothesline stepped away from a pole like a thin horizon. A citrus tree leaned toward a low table as if sharing news. The smell of soil rose clean and friendly; a later barbecue rumor hung under it, charcoal and faint sweetness.

The lantern’s light walked ahead and marked the stones. Fish-shapes swam across bark and dirt. At the far end, a small wooden gate showed a latch that belonged in stories with rabbits and cousins. Beyond the slats, something glinted—paper? Glass? Or the sense of a threshold doing its old job.

We stepped into somebody’s garden, Mei Lin said. We say sorry to the air, we go back through the hedge, we knock like decent people next year, and we admire the orange tree from the sidewalk.

She turned toward the way they came. The hedge offered leaf and more leaf. No gap. The flashlight found a web stretched taut between two twigs, silver as a violin string. She moved left, then right. Leaf, leaf. The kind of illusion that shows up in dreams and old stories, then in a mother’s practical field of vision, unwanted but undeniable.

June reached the gate and rested her hand on the latch. She glanced back the way children do when they hear a rule go by: a little apology, a little plea, a little dare.

Please, she said, half to the gate, half to the lantern, half to her mother. The lantern drew itself thin, a breath before a note. Somewhere a dry leaf let go and landed with a sound like a page turned in another room. The citrus tree gave up one fruit with a soft thump, as if punctuation gathered and dropped.

You hear that? June whispered. It sounds like Nai Nai.

June had never heard her grandmother sing in life. That claim reached Mei Lin like a coin slid across a table in a quiet bar—small, definite, heavy. She remembered her mother’s humming—the steam of rice, the low radio in typhoon season, the neat brushwork of a name on red paper. She remembered how her mother distrusted masks and handed out extra candy anyway because children count when you tally a life.

The flame leaned toward the latch again. A small wind pushed against Mei Lin’s cheek, no colder than a sigh. She measured options in the space of three heartbeats—pull June back and fight the hedge with elbows, knock on a stranger’s back door and test the kindness of whoever lived here, or open the gate and walk two steps forward in the confidence of those who mind their manners even in strange places.

Mei Lin placed two fingers under the lantern’s base to keep it level. The flame rose, bowed, steadied. Permission, or imagination dressed as etiquette. June lifted the latch. The wood gave with a dignified groan, old but willing.

Beyond the gate, an alley ran between fences, the kind utility crews use, the kind kids name and own until adults find out. Tonight the alley wore a different skin. Paper awnings leaned from thin poles. Steam drifted from bamboo baskets fat with buns. A small stall showed a tray of candied hawthorns gleaming like rubies. Red squares of paper clung to posts, each brushed with a single character in a hand that trusted ink. A woman at a low table poured tea into cups thin as eggshells. Somewhere a strummed melody threaded the steam and tied a knot in Mei Lin’s throat.

June’s eyes went wider than the hoodie allowed. She lifted the lantern higher. The fish threw comets onto stone and wood. The flame bowed to the tea table, then to the candy, then to the hawthorns. No one looked up at them with surprise. No one pretended to ignore them. The alley simply made room the way a long table makes room when late guests arrive.

We can’t— Mei Lin started, habit reaching for the sentence that rescues order. Then the woman at the tea table lifted a cup and spoke Mei Lin’s name in vowels that came from her mother’s mouth and no other.

Mei Lín, the woman said, as if greeting a girl home from school.

The sound reached into the place under Mei Lin’s sternum where duty sits and loosened a knot she hadn’t named. June’s hand found hers. The lantern warmed her wrist.

We came out for candy, Mei Lin said, voice careful, breath not steady. We should go back. Mr. Delgado waits with chocolate.

Then take a sip first, the woman said, and her smile held sternness and mercy in equal measure. A sip for the road that brought you. A sip for the road that takes you home.

June looked up. Mom, can we sit? The lantern likes her.

Lanterns don’t like— Mei Lin began, then stopped. The words felt thin, like paper left in rain.

She guided June to the low table. She sat. The cup fit her hands. Heat climbed into her wrists, into her forearms, into the part of her that never warmed during office days under humming vents. The tea smelled of stone fruit and an honest smoke. The woman adjusted Mei Lin’s cardigan cuff, tucking the snag where it wouldn’t catch on a drawer again.

You keep too many lists, the woman said, not unkindly. Lists keep you alive. They also keep you from certain corners where blessings wait without appointments.

I have a child, Mei Lin answered. I choose corners with good lighting.

The woman nodded. Good lighting helps. So does a lantern that remembers who loves you.

Steam braided with candle smoke. For a moment the fish windows filled with small faces—cousins, aunties, a neighbor who once loaned sugar and returned the bowl with oranges, a choir friend with a high laugh. The faces flickered and softened and then pulled back like tide.

Mei Lin tasted the tea. Warmth settled the tremor in her hands. June leaned the lantern toward the cup as if offering drink to a shy guest. The flame bowed politely. Somewhere, closer than before, a melody leaned into a phrase Mei Lin knew: the little tune her mother hummed when hems came straight on the first try.

Mr. Delgado waited in his driveway. The street would keep its small safety. Dumplings sat under a towel, patient. Work files waited with their tidy threat. All of that still held.

Here, something else held.

Mei Lin set the cup down and looked at the woman. What do you want from me?

Remember without fear, the woman said. Feed the hungry. Leave water. When the wind bends a small flame, assume breath, not danger.

The lantern’s fish swam their light along the tabletop, then toward the gate again, as if currents turned. June squeezed her mother’s hand, excited but calm, the way children look when wonder finally answers to trust.

Mei Lin stood. She bowed—habit, gratitude, lineage, all in one quiet bend. The woman poured another cup and set it aside, untouched, the way you set a place for someone you love who may or may not arrive.

They followed the lantern’s steady pull back to the wooden gate. The hedge offered the gap again, casual as a yawn. The sidewalk accepted them without comment. Across the street, Mr. Delgado poured from his thermos and lifted it as if to say, Took your time, good. Some walks deserve time.

Where did you vanish? he called.

We met friends, June said, solemn.

Mr. Delgado nodded as if that answer matched a truth he already owned. Take two chocolates, he said. The road home sometimes stops at your door and asks for a tax.

They crossed. The lantern burned like any good candle now—no mischief, no lean, only work. Mei Lin felt the warmth on her palm where the handle pressed. She unlocked their door. Inside, the apartment smelled of vinegar and soy and the faint vanilla of the earlier candle. She reheated the dumplings, crisped the edges in a pan until they sang. June ate three and reached for half of a fourth. Mei Lin set the orange and the water on the table and slid a small wedge near the window. The candle on the sill bowed and straightened, polite.

June fell asleep with the hoodie ears askew, hair charged from dry air, one hand on the lantern handle as if holding a friend’s fingers on a bus. Mei Lin tucked the blanket around her and stood in the doorway and counted the things within reach that mattered: breath, food, a neighbor who bakes, a phone number she can call when superstition demands company, a child whose faith carries light without arrogance.

She set the lantern on the piano bench where red envelopes waited in a neat stack. The fish looked up through their cut windows. Mei Lin touched the handle once.

Rest, she said.

The flame steadied, then settled, as if sleep also comes to those who carry others.

Act II — The Crossing

The alley did not end.

It curved, the way music curves when it chooses one more note.

Steam lifted from baskets shaped like small moons; the air smelled of sesame and sweet rice, of iron skillets and sugar just past its breaking point. Lanterns—hundreds of them—hung on invisible strings, swaying as if the night itself inhaled and exhaled.

June walked ahead, fearless, her paper lantern held high among the others. Its painted fish glowed brighter now, swimming with companions it had never met. She kept glancing back, checking that her mother still followed. Mei Lin followed, of course. Habit could be love in motion.

A seller at the nearest stall spooned out dumplings glistening with broth.

He looked up at Mei Lin and nodded as though she were late for a shift.

“You’ve been gone a while,” he said, voice a rasp of warm wind.

She meant to answer—I don’t know this place—but found herself nodding back. The dumplings steamed exactly as hers did at home, one edge thicker, the fold a little rushed. Someone had copied her imperfection and honored it.

June tugged her sleeve.

“Mom, look—fish candy!”

A tray held sugar animals so delicate that breath alone could melt them. She lifted one, and for a heartbeat Mei Lin feared it would dissolve between her daughter’s fingers. Instead it shimmered and swam in air, tail flicking.

The vendor winked. “Every story wants sweetness,” he said, then turned to serve the next invisible customer.

They walked deeper.

The alley widened into a courtyard bordered by paper walls that trembled but did not fall. A fountain murmured at its center—clear water over smooth stones. In its ripple Mei Lin saw faces: her mother in a red scarf; her father bending over a typewriter that never came to America; the nurse who held June when she was born; Mr. Delgado smiling through steam from his thermos. Memory had learned geography.

“Why did they come?” Mei Lin asked under her breath.

“To see who remembers,” the woman at the tea table said behind her, though the woman had not walked. She simply was there.

The teapot rested where Mei Lin’s shadow ended.

“You feed them, they fade gently. You fear them, they stay hungry.”

“I’m not afraid,” Mei Lin said, though her heartbeat argued.

“I’m tired. That’s different.”

The woman smiled. “Tired hearts hear best. Sit.”

She poured again. The liquid shone amber. Mei Lin sat.

June perched beside her, the lantern between them, light caught in her hair.

“You keep the living alive,” the woman said. “Let us keep the living whole.”

Mei Lin frowned. “I don’t understand.”

The woman dipped a fingertip into the tea and drew a circle on the table. The mark glowed a moment, then faded.

“Whole means remembering even the parts that ache. Half-memory—what you call practicality—hurts longer.”

June reached across the table, tracing the same circle with her small hand. “Like closing a story with no ending,” she said.

Her mother looked at her, startled. The girl’s voice had the calm of someone quoting something ancient.

The woman nodded approval. “Every child knows. Adults rehearse forgetting.”

From somewhere beyond the walls came the faint clang of a bell. One, then another. The sound rippled through the market like water hitting glass. Vendors began to pack their stalls without hurry. The air cooled.

“What happens now?” Mei Lin asked.

“Morning,” the woman said. “Markets of memory close before dawn. Go while your light still listens.”

Mei Lin stood. June stood. The woman reached out once more and fixed the ribbon on the lantern’s handle—tightened, smoothed, let go.

“Teach her to bow when she thanks the air,” she said. “That’s all the gods ever asked.”

They walked. Each stall dimmed as they passed. Sugar cooled, tea ceased steaming, paper moons folded back into dusk. The hedge waited ahead, the gap now clear. As they stepped through, the music behind them gentled into silence, not an ending but an echo finding rest.

Sycamore Street again—quiet, domestic, unchanged except for a hush that understood them. Mr. Delgado’s thermos gleamed across the way. The dog two houses down barked once and surrendered to sleep. A sprinkler ticked faint applause.

Mei Lin looked at the lantern. The flame behaved itself—ordinary, unpossessed—but its glow felt wiser, like a word learned in two languages. She exhaled and felt the warmth answer through her palm.

They crossed toward home. June hummed a melody Mei Lin recognized from her childhood—the same tune the woman had played with silence in the market. Each note balanced between worlds, a bridge too slender for fear.

Act III — The Bargain

Dawn did not arrive all at once. It slipped in by degrees—first through the thin crack of the blinds, then along the wall where paint had dulled with years of rent, finally into the kitchen where last night’s tea cooled in forgotten cups.

Mei Lin woke before the alarm. Habit, not rest, raised her. For a moment she listened for ordinary sounds: the pipes tapping, a car reversing, the slow rhythm of her daughter’s breath. All accounted for. Yet the silence between each sound carried something else—a patience, a waiting. The same hush that had followed them from the alley.

On the piano bench the lantern still burned, though she had snuffed it. Its paper skin glowed faintly, as if remembering light. She crossed the room, half expecting heat. Instead she felt warmth steady as pulse.

“Dream?” she whispered.

June stirred on the couch, small under the blanket. “They said thank you,” she murmured, not quite awake. “The hungry ones. They liked the orange.”

Mei Lin froze mid-breath. A child’s dream, she told herself. Children dream easily. But a small bowl on the table—empty last night—now held a single orange peel curled like a signature. The water glass had fogged from the inside.

She sat, elbows on knees, staring at her own reflection in the windowpane. The woman who stared back looked the same: cardigan, tired eyes, a forehead that had learned to measure worry in centimeters. Yet behind her reflection flickered the outline of stalls and hanging paper moons, visible only when she didn’t blink.

“What do you want from me?” she said softly to the glass, to the outline, to whatever listened.

The air answered without sound, only a pressure that felt like the touch of her mother’s hand smoothing her hair before school.

“Remember without fear,” the memory voice said. “Feed the living, honor the gone. That balance keeps the bridge open but steady.”

She nodded as if receiving instructions from a foreman. “All right,” she said aloud. “But I have work, a child, deadlines.”

The window gave back her words multiplied and thinner. She imagined the alley beyond the hedge still existing, folding dumplings for ghosts who clocked out at sunrise.

June padded over, rubbing her eyes. “Are we late?”

“Not yet,” Mei Lin said. She poured milk, cracked two eggs into a pan, moved with the choreography of morning. Between clatter and sizzle, she felt the presence quiet but not retreat.

When she set the plates down, June smiled at her. “Mom, we could make a lantern every week. Like a promise.”

Mei Lin almost said no—schedules, time, glue—but stopped. The word promise balanced on the edge of the table like an orange about to roll.

“We could,” she said. “Each one for someone who helped us, maybe.”

“Like Mr. Delgado?” June said.

“Like him. Like Auntie Rui. Like Nai Nai.” Saying the name felt easier this time, like stepping onto familiar ground that no longer shook.

They ate. The eggs vanished quickly; the quiet stayed. Outside, the street returned to its weekday costume—leaf blowers, delivery trucks, a jogger with bright headphones. Nothing eldritch in sight, unless you counted the thin veil of morning mist curling through sycamore branches.

When they finished, Mei Lin carried the plates to the sink and paused. Water ran clear, but steam from the pan rose in shapes that almost—almost—resembled written strokes. The first character for her own name appeared, then dissolved. She touched the counter’s edge to steady herself.

“Okay,” she said, half to the air. “I hear you.”

That night, after work and homework and another round of dumplings, she lit the lantern again. The fish flickered in gold and copper. She set a glass of water beside it, a slice of orange, a folded scrap of paper with a name—her mother’s—written in blue ink. The flame leaned toward the paper and stilled.

This, she understood, was the bargain: not payment, not superstition, but participation. She would keep the small gate open—not to the dead, but to memory. In return, memory would keep her from turning to stone.

Outside, Mr. Delgado played old boleros on a tinny radio while watering his lawn. The sound wandered through the window screen like a lazy guest. Mei Lin smiled. She’d make him extra dumplings tomorrow.

June peeked into the room. “Lantern time?” she asked.

“Yes,” Mei Lin said. “Lantern time.”

They sat together on the floor, cross-legged, faces lit by the trembling light. June whispered names she barely knew; Mei Lin repeated them, one by one, until each syllable felt repaired. The paper fish swam slow circles on the wall.

When the candle sank low, Mei Lin lifted the lantern and whispered something she hadn’t said in years—a line her mother used during power outages: Light doesn’t disappear; it only travels.

And as the wick gave its final breath, Mei Lin felt the room brighten in some deeper register, unseen yet certain, like the first thought before words arrive.

Act IV — The Return

By morning, the neighborhood remembered itself. Trash trucks rumbled. School bells clanged faintly from down the hill. The air smelled of coffee and the faint perfume of last night’s smoke.

Mei Lin opened the curtains wide. Light streamed across the piano bench where the lantern rested, now dark and harmless—just paper, glue, and wire. Yet the way it caught the sun felt deliberate, as if it still considered its old duty.

June shuffled out of her room with a backpack and the sleepy confidence of the newly brave. “Mom, I told the kids we have a secret lantern. It keeps good dreams.”

“That so?” Mei Lin asked, tying the last knot in June’s ponytail. “Then we’ll feed it another good dream tonight.”

The girl grinned, hugged her, and ran down the walkway toward Mr. Delgado’s waiting wave. The scent of pan dulce rode the air again, folded neatly into the ordinary.

When the door closed, Mei Lin stood a moment, palms on the counter, eyes on the lantern. In daylight it looked fragile, almost foolish—a craft project that should have sagged overnight. Yet it held its shape, faintly gold where the paint thickened.

She thought of the market behind the hedge: the steam, the hum, her mother’s voice offering tea. No terror, only tenderness misfiled under fear. She understood now that she had not wandered into another world; she had wandered deeper into her own.

She sat at the table and wrote on a scrap torn from yesterday’s affidavit pad:

Eldritch — the moment when the familiar remembers its soul.

Then beneath it:

Not ghost. Not trick. Memory in its true clothes.

She pinned the note to the refrigerator beside grocery lists and a dentist reminder. Let it live among errands; that was where revelation belonged.

Later, she would pick up June, buy new candles, cook rice with orange zest, and text Auntie Rui that the lantern had worked “just fine.” She would fall asleep to the small sound of wind at the window, no longer dreading it.

For now, she poured herself tea, breathed the steam, and felt the faintest shift in the room—as if unseen hands straightened the snag in her cardigan cuff again.

The light through the blinds flickered once, not with warning but with affection. The apartment exhaled.

Word Unveiled Reflection

Eldritch, she learned, never meant monstrous or strange. It named the narrow border where the known leans toward the remembered, where mercy wears the mask of mystery. To live with such light is not to fear the unseen, but to greet it—head bowed, heart open—as part of one’s own unfinished love.