The Exit

The applause began before Malcolm Dorsey finished his sentence.

He stood at the center of the glass-walled atrium that had once been a drafty warehouse and was now a monument to his own restlessness: steel beams, warm wood, discreet art, the faint hum of servers like distant bees. Above him, the Dorsey Systems logo glowed in soft white, already scheduled to be replaced by the acquiring conglomerate’s more muscular brand.

“…and whatever this company becomes next,” he said, pausing for a beat he no longer needed, “I’m proud of what we built together.”

The crowd rose to its feet. Engineers in hoodies, product managers with careful smiles, executives in deliberately casual jackets. Someone popped another bottle of champagne; the cork ricocheted off a beam and drew a ripple of laughter. Phones lifted. A few people wiped at their eyes with the backs of their hands, surprised to find the gesture necessary.

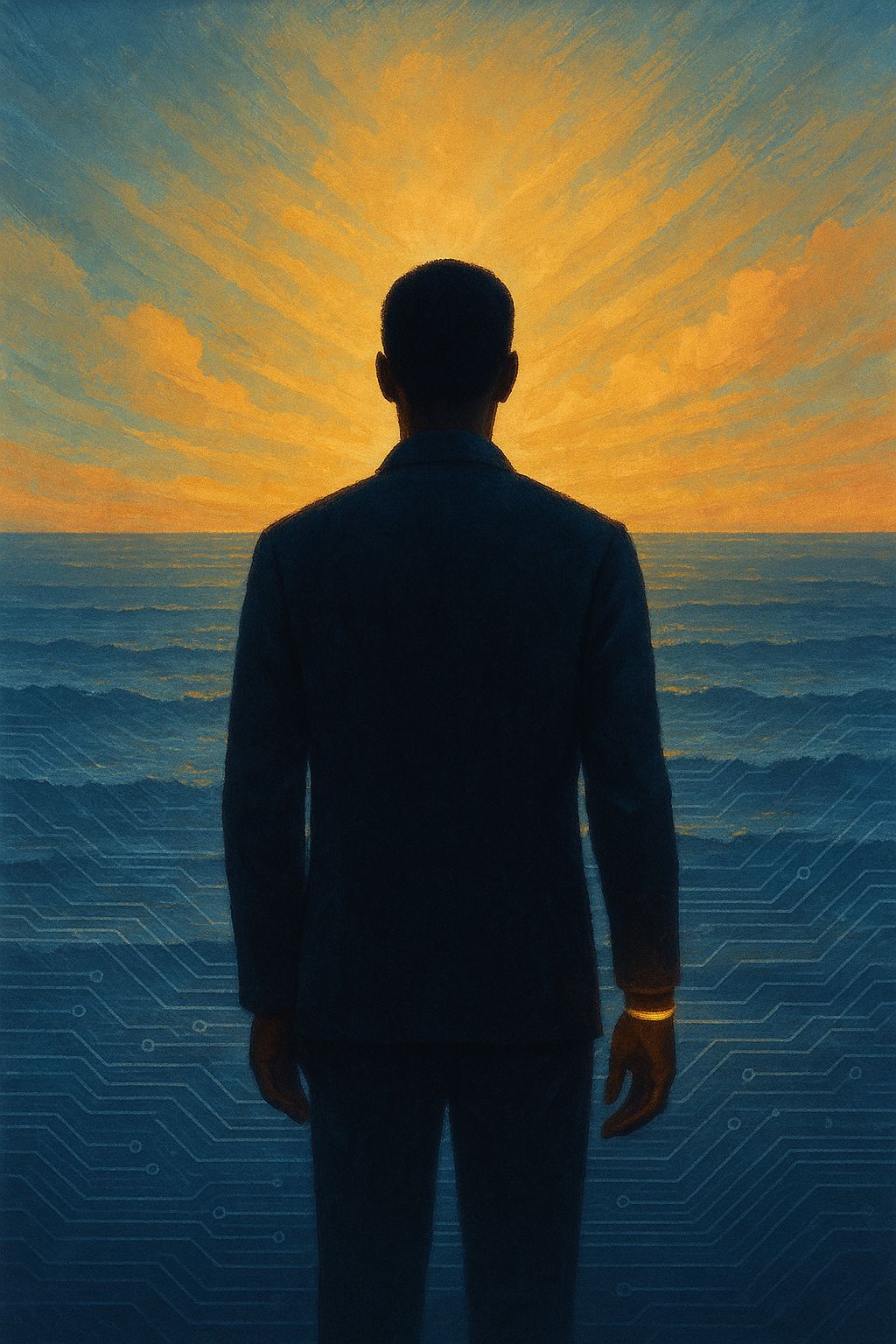

Malcolm smiled, because this was the moment he was supposed to smile. The face on the internal livestream looked composed, a man at peace with walking away. Inside, though, he felt not the hum of a machine shutting down but the sudden hush that follows a wave’s collapse — energy spent, the shore still trembling.

He stepped away from the mic to the chorus of congratulations. Hands gripped his. A young engineer with a nose ring said, “You changed my life, Mr. Dorsey.” A VP clapped him on the shoulder and whispered, “Legend.” HR presented him with a framed early product sketch he barely remembered drawing. People were already nostalgic for a past he hadn’t had time to feel.

“Sam—Malcolm.”

He turned. Lottie corrected herself mid-syllable, laughing softly — a private echo from the years when she’d called him Sam for “Samson,” her name for the way he threw himself against obstacles. She touched his lapel, smoothing a fiber that wasn’t there.

“You did well,” she said. “You even sounded like you meant it.”

“I almost did.” His voice carried just enough amusement to make it safe.

She looked radiant, as she always did in a room full of people: cream silk blouse, tailored trousers, silver hair styled with studied ease. Fifty-two and luminous, she moved through space as if she’d negotiated with gravity and won. Her eyes, though, flickered past him toward the view beyond the glass — Palo Alto receding into dusk, taillights in thin red strings, planes lifting off from SFO like fireflies tracing their routes home.

“Do you realize,” she said, looping a hand through his arm as they drifted toward the balcony, “this is the first time since I’ve known you that your calendar isn’t a battlefield?”

He smiled. “Give the lawyers a day. They’ll find something.”

“No.” She stopped him gently on the threshold, where the conditioned air met the cool breath of evening. “I mean empty. Open. Yours.”

He followed her gaze. The campus looked smaller from here, almost modest. Buildings he’d obsessed over now blended into the larger landscape of tech architecture: glass, steel, the theater of transparency. Beyond that, the hills held their shape, indifferent.

“What do you want to do?” she asked.

He had been asked that question all week, usually by bankers. Start another company? Join a board? Write a book? Mentor founders? His answers had been competent, vague, acceptable. Tonight, none of them felt close enough to touch.

“I suppose,” he said, “I should figure out who I am when I’m not copied on everything.”

Lottie laughed, but her hand tightened on his arm. “I’ve been thinking,” she said. “We should leave. Not just for a week. Properly leave. Paris, London, Rome, maybe Lisbon. A year, at least. See the world before we’re too creaky to enjoy the good walking cities.”

He looked at her profile, the familiar angles softened by the balcony lights. Travel had always been a promise deferred — another funding round, another launch, another crisis. They had postcards from places she’d gone without him, tucked into cookbooks they never used.

“A year,” he repeated.

“Yes.” Her eyes were bright now, not with tears but anticipation. “We’ve spent decades watching the world through screens and quarterly reports. I want to see it up close. People, art, music. Old streets. New conversations. No one calling you at three in the morning because a server farm in Ohio refuses to wake up.”

He considered the idea, turning it over like an unfamiliar object. A year without being necessary to something humming and fragile. A year where silence could mean peace instead of failure.

“What would I do?” he asked lightly.

“You could try this radical thing I’ve heard of,” she said. “It’s called living.”

He chuckled, but the word unsettled him. Living implied that whatever he’d been doing up to now was something else — rehearsal, maybe, or a very elaborate detour.

Behind them, another cheer went up as someone started a slideshow of old company photos. The early days: secondhand desks, bad lighting, too much caffeine, a younger version of him in a T-shirt with a slogan he would not wear now. He watched himself on the screen throw his head back in laughter at some forgotten joke, arms wide, as if claiming the future by gesture alone.

Lottie nudged him. “Look at him,” she said softly. “He thought this was the whole story.”

“And now?”

“Now,” she replied, “we get to find out if there’s another chapter. Maybe even the better one.”

He didn’t answer right away. The sky over the hills darkened from cobalt to ink, the first stars faint against the leftover light. In the atrium behind them, his team toasted the deal that had made him unimaginably rich and, for the first time in years, profoundly optional.

“We’ll go,” he said at last.

She turned to him, surprised by the steadiness in his tone. “You mean it?”

“Yes.” He felt the decision settle into him like a weight and a release. “Book it. The whole cliché. Paris, London, Rome. Anywhere you want.”

She kissed his cheek, quick and pleased. “You won’t regret it,” she said.

He watched his younger self smile again on the screen, pixelated and earnest, and for a flicker of a second, thought he saw in that face both the promise and the cost of all he’d built.

London: The Beginning of Distance

London greeted them with drizzle and understatement. The air smelled faintly of wet stone and diesel, and the Thames moved like a thought half-finished. From their hotel window near Blackfriars, cranes swung methodically over the skyline, metronomes of progress marking a rhythm Malcolm could still hear inside himself.

Their first morning together was briskly polite. She had museum tickets in hand before breakfast; he was already answering emails he had promised to ignore. By noon, they’d divided the day as if by instinct — she to the Tate Modern, he to the TechFront accelerator in Shoreditch.

At the accelerator, a mural of circuitry stretched across one wall, bright as graffiti. The founders looked impossibly young, talking in acronyms and caffeine. They greeted him with reverence, a living footnote in their creation myths. Pioneer, they called him — a word that felt like both medal and headstone.

A boyish CEO asked if he missed the rush of relevance.

Malcolm smiled. “Sometimes the rush outruns the reason.”

The young man nodded, polite but puzzled. When Malcolm shook his hand, he noticed the callouses were from weight training, not work.

Crossing the bridge later that afternoon, he watched the gray water curl around its own current. The city hummed — buses sighing, sirens threading through traffic, street vendors calling from under umbrellas. He realized the sound reminded him of the server rooms back home — relentless, unseen, indispensable.

Across the river, Lottie stood before a Rothko — color bleeding into color like quiet argument. A curator named Amelia, bright and angular, invited her to lunch. At a café overlooking the embankment, they spoke of abstraction and attention, of how commerce had stolen art’s nerve. When Amelia called her vital, Lottie felt herself uncurl, warmed by recognition that had nothing to do with love and everything to do with being seen.

That evening they reunited at a restaurant near Covent Garden, all reclaimed wood and candlelight. The air smelled of truffle oil and the low murmur of couples speaking softly. For a while, the talk was easy — the museum, the accelerator, the weather’s indifference.

“I met a few people today,” she said finally. “They’re organizing a salon in Paris — writers, critics, thinkers. I might help host.”

He nodded. “Sounds interesting. I met some founders from Nairobi. They’re building a platform to teach coding in local dialects. They asked if I’d advise.”

She tilted her head. “So even now, you’re finding another company.”

“And you,” he said gently, “another stage.”

She laughed too quickly, touching his hand in reflex rather than affection. The candlelight trembled between them, flickering in the small current of her movement.

He looked down at his watch — not to check the time, but to give his silence somewhere to go.

Outside, London’s drizzle turned to steady rain, the streetlights shimmering in blurred halos. Inside, their reflections floated in the window glass — close enough to blur, too far to touch.

Paris: The Divergence

Paris opened before them like a film already in progress — all motion, color, and the faint scent of something living too well. Their rented apartment overlooked the Seine, where light moved across the water with a kind of practiced charm. Lottie adored the view; Malcolm admired the engineering of the bridges.

In the beginning, they moved together. Mornings at cafés, afternoons wandering through markets where time slowed long enough for them to pretend it still belonged to them. But soon, the rhythm that had once bound them began to fracture into separate cadences.

Lottie met Adrien Duval at a gallery opening in Le Marais — a French-Moroccan architectural historian with a poet’s diction and a collector’s patience. He spoke of façades as if they were memories, of columns that leaned into history like old lovers. He listened to her stories with a stillness Malcolm had long abandoned. When he called her curious in the best way, something in her — dormant since her thirties — woke up. She began to wear color again.

Malcolm noticed. He also noticed how her laughter now carried new vowels — softer, Parisian. Yet he couldn’t bring himself to resent it. He had once loved the same quality: her ability to absorb a place and reflect it back as light.

While she found attention, he found silence. A week later, over bitter coffee and a headline about global innovation, he met Kofi Mensah — a Ghanaian robotics entrepreneur with the kind of earnestness that cuts through cynicism. Kofi spoke of democratizing prosthetics using recycled tech: “If we can make machines learn compassion, maybe we’ll follow.”

The line stayed with Malcolm all day.

He began spending mornings with Kofi’s team in a borrowed workspace near Montparnasse — a basement humming with code, laughter, and optimism unscarred by markets. For the first time in years, he felt small in the right way.

Lottie, meanwhile, attended lectures, salons, and dinners. Her social calendar began to look like a second passport. She sent Malcolm reminders of events he rarely attended, though she always said we.

One evening, he returned late to the apartment. Adrien’s voice lingered faintly on the speakerphone; she ended the call too casually. The air between them thinned.

“You still live by quarterly returns,” she said, her tone sharp with exhaustion.

“And you,” he replied, “live by who’s watching.”

The silence that followed was longer than the argument that never came. Through the open window, the Seine kept whispering its endless persuasion — that all things flow away eventually.

Rome: The Breaking Point

Rome shimmered like a fever dream—sunlight on stone, the hum of scooters beneath the drone of doves, beauty rehearsing its ruins. They arrived in late May, when the air felt perfumed with dust and memory. For a time, the city disguised their drift. Beauty can do that—it flatters what’s breaking.

They moved through the days like travelers playing versions of themselves. Morning espresso at the corner café. Photos at the Forum, smiling because history required it. Evenings of polished conversation—wine, candlelight, curated ease. Lottie captioned their pictures with fragments of poetry. Malcolm scrolled through them absently, noting that even happiness, once filtered, began to resemble marketing.

At night, the ceiling fan hummed a tired rhythm in their flat near Trastevere. She read until midnight, her lips moving faintly around French phrases she had begun to prefer. He mapped outlines for a mentorship network he might fund in Nairobi, lines of code scrawled into a notebook as if writing could keep him necessary. They were two devotions running parallel—hers to attention, his to usefulness.

Sometimes, she would glance at him from her book and almost speak. Then she would close it instead, as if silence were safer.

One evening, Lottie stood before the mirror, fastening an earring. The gown was bronze silk, backless, unapologetic. The reflection staring back at her was confident, almost defiant, yet she caught a small tremor in her wrist as she adjusted the clasp. For a moment she saw herself as Malcolm once did—curious, luminous, untiring. Then the image shifted, and she saw only the woman determined not to fade.

“You’re sure you won’t come?” she asked without turning.

“I have a call with Kofi’s group in the morning,” he said. “Different kind of soirée.”

She smiled at her reflection. “Ghana,” she said, tasting the word. “You’re retiring into charity now?”

He looked up from the desk. “No,” he said evenly. “I’m retiring into relevance.”

Her laughter, light and edged, filled the room like perfume—pleasant at first, then cloying. She touched his shoulder as she passed, a gesture practiced into civility, and left the faint scent of citrus and resolve.

When she was gone, the apartment felt overlit. He wandered onto the balcony and watched the city pulse below: headlights sliding through narrow streets, a violin’s stray note floating up from the piazza. He imagined her walking into the Villa Medici, radiant under chandeliers, her laughter absorbed by marble. The thought hurt less than it should have.

Near midnight, he saw her name appear online—tagged beside Adrien’s in a cascade of photographs. She stood beside him, glass in hand, her smile exact, her posture fluent in attention. Adrien’s fingers rested at the small of her back. The image glowed on his tablet like an icon of another faith.

Humiliation flared, clean and precise. But beneath it came an unexpected stillness—something like surrender, but not defeat. Perhaps this was what letting go truly felt like: the ache without the argument.

He sat for a long time, watching the Roman night dissolve into its own light. In the quiet, he realized their marriage had become tourism—checking boxes, collecting views, avoiding silence. They had mistaken movement for meaning.

When dawn came, the sky was a pale watercolor of smoke and gold. Church bells tolled across the river. A baker’s cart rattled over cobblestone, the air fragrant with yeast and exhaust. He packed one bag: a few shirts, his worn notebook, the watch Lottie had given him years ago—the only timepiece he never learned to ignore.

Before leaving, he paused by her side of the bed. Her gown from the night before lay draped over a chair, bronze against the morning light. He folded it carefully and placed it beside her perfume on the dresser, a small courtesy to the past.

By the time she returned, barefoot and slightly drunk, the suitcase waited by the door.

“You’re actually leaving,” she said, mascara feathered into irony.

“I am.”

“Where?”

“Accra.”

She blinked, then gave a single incredulous laugh. “Of course you are.”

He nodded. “The flight’s at six.”

He stepped into the hallway as the first bells finished their echo. The city was waking—priests crossing squares, shutters opening, pigeons rising. He wasn’t praying, yet he bowed his head all the same.

Accra: The Encounter

The heat in Accra arrived like an announcement — not oppressive, but certain. It carried the scent of rain on red clay and something faintly sweet, like mango ripening in the sun. Malcolm stepped from the airport into a city that moved to its own percussion: horns, laughter, street radios, the overlapping beat of survival and song.

By the time he reached the conference center, the air-conditioning felt almost alien. Rows of banners proclaimed The Ethics of the Algorithm. His keynote was scheduled last — a position of respect, or exhaustion. Either way, he preferred it. He spoke of responsibility, of technology as mirror and maker. He kept his tone calm, his words precise. When he finished, the applause was courteous but curious; most had come to see what the celebrated founder would say now that he was no longer building anything.

The moderator, Dr. Celeste Okafor, thanked him and leaned toward the microphone. “You’ve taught machines to recognize emotion,” she said, her voice low and measured. “Did you ever worry they’d recognize it better than we do?”

The audience laughed. Malcolm didn’t.

He looked at her — early forties, Nigerian-American, poised without effort. Her eyes held warmth, but also a certain diagnostic clarity. “Every day,” he said.

A silence rippled through the room, not awkward but attentive. She nodded, satisfied, as if he had just passed a test that few knew was being given.

After the session, she found him in the lobby, balancing a paper cup of coffee like an afterthought. “You didn’t dodge the question,” she said. “That’s rare.”

“I used to think answers made me credible,” he replied. “Now I prefer to be accurate about my ignorance.”

Her smile was small but approving. “Walk with me.”

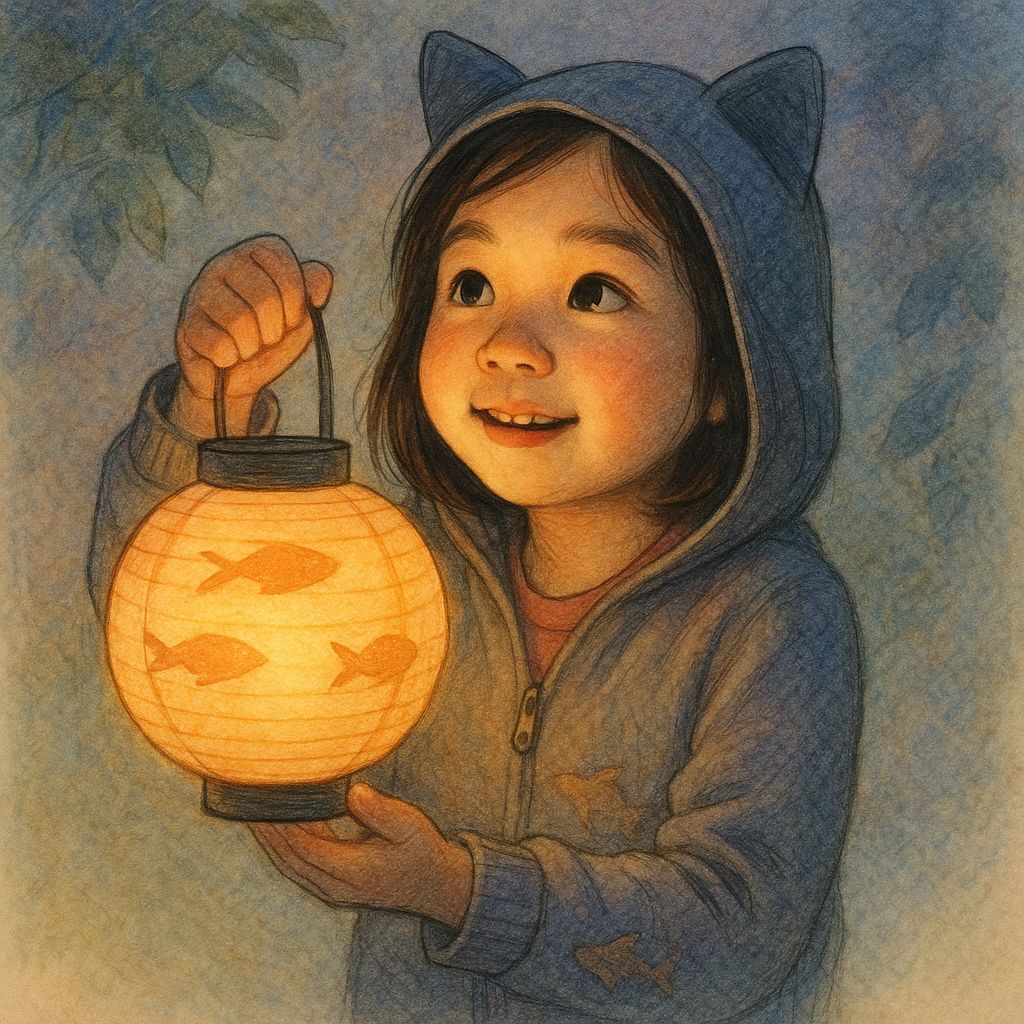

Outside, the streets pulsed with late-afternoon heat. They wound through Makola Market, where stalls overflowed with color — fabrics bright enough to rewire the heart, vendors calling prices with musical precision. Celeste greeted people by name. A boy handed her a bracelet woven from copper wire. She gave him a coin and slipped the bracelet onto Malcolm’s wrist. “To remind you that connection can be handmade,” she said.

They walked on, talking not about profit but pulse — how algorithms were reshaping the informal economies that kept the city alive. She spoke of data colonialism and empathy as infrastructure. He listened — not to content, but to cadence. Each word felt grounded, deliberate, human.

By the time they reached the edge of the market, the sun was falling into the Atlantic, enormous and unhurried. The light turned the air gold, and for the first time in years, Malcolm felt something he didn’t immediately want to name.

That night, in the quiet of his hotel room, he opened a notebook he hadn’t used in decades. He wrote one line before setting the pen down:

“Perhaps what we call innovation is only remembering what we’ve forgotten to feel.”

He closed the book and left it on the table — not finished, but begun.

The Village Visit

The road out of Accra unspooled in long, rust-colored ribbons, the air thick with diesel and promise. Celeste drove the old Land Cruiser with one hand, gospel static murmuring from the radio. Every few miles she slowed for goats, for children carrying buckets, for men pushing bicycles heavy with plantains. The rhythm of the journey was human, not mechanical—pause, wave, continue.

“You’re quiet,” she said.

“I’m listening,” he replied, eyes on the horizon.

“To what?”

He smiled faintly. “Everything I used to filter out.”

She laughed, rich and quick. “Good. Then you’re almost ready for the field.”

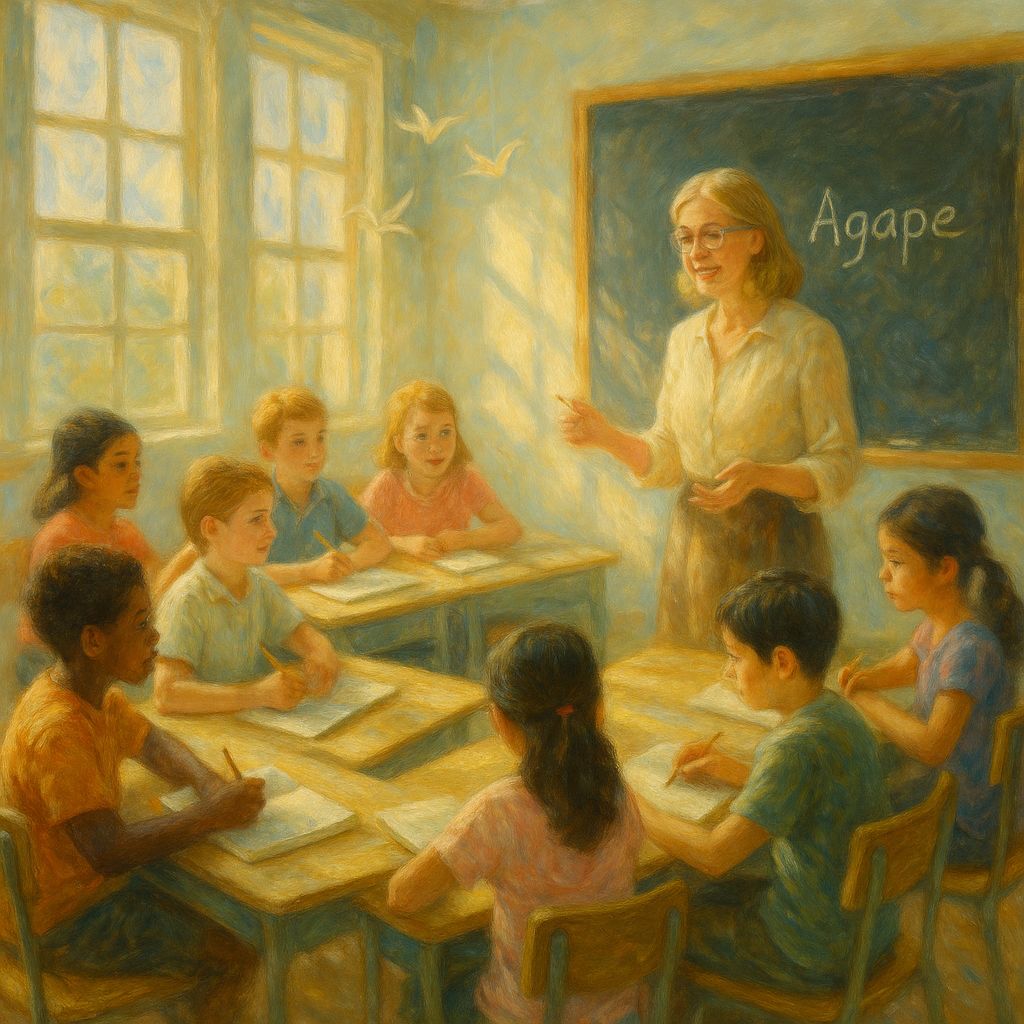

After two hours, the city thinned into forest and light. Palm fronds shimmered like coins; the sea wind carried salt and woodsmoke. Celeste turned down a narrow track where the soil blazed the color of brick dust. The school appeared suddenly—three low buildings painted an ambitious blue, their walls patched by hand. On the front, someone had scrawled in chalk: Code the Future.

“This is one of our hubs,” she said. “We started with two tablets and too much faith.”

Inside, the heat was thick but joyful. A dozen children huddled around mismatched screens, faces lit by the glow of learning. The hum of a sputtering generator filled the room like a heartbeat. Their teacher, Ama, greeted them with a smile that belonged entirely to the moment.

“Professor Dorsey,” Celeste said, teasingly. “Meet my favorite innovators.”

The children giggled. A boy, barefoot and fearless, tugged Malcolm’s sleeve. “Sir, watch.” He tapped a few commands on a cracked tablet. A small robot—made from a soda can and salvaged wheels—rolled forward with a hiccuping whirr. Laughter erupted.

Malcolm knelt beside the boy, sweat beading on his temple. “How’d you power it?”

“Old phone battery,” the boy said. “Still works.”

He nodded slowly. “Still works,” he repeated, the phrase feeling truer than it should have.

Celeste moved through the room like quiet current—checking connections, translating when Ama’s English slipped into Twi. She leaned toward Malcolm. “When I left academia, my department chair told me I’d vanish. That no one writes footnotes about hope.”

He looked at her. “And yet here you are—published in dust.”

She smiled. “The most peer-reviewed medium there is.”

Outside, the afternoon boiled. They sat beneath a baobab tree, sipping tea that smelled of ginger and smoke. The enamel cups burned their fingers. A radio in the distance played highlife music, its bright guitar skipping over the hum of the generator.

Celeste poured another cup. “These children think coding is like storytelling. They don’t separate logic from rhythm. They build because it feels good.”

He leaned back against the tree trunk, the bark warm through his shirt. “In my world, we coded to escape the feeling part.”

She watched the wind move through the branches. “Maybe you needed to leave your world to remember it.”

He laughed softly. “You sound like a sermon.”

“I left sermons for systems,” she said. “But they keep finding me.”

The generator coughed once, then went silent. A groan rose from inside. For a moment, the air held its breath. Then a girl of about ten—barefoot, determined—picked up a stick and began drawing code into the dirt. Her classmates joined, reading the commands aloud like a chant: If light, then move. If sound, then dance. Their voices rose and fell with the rhythm of possibility.

Celeste’s hand brushed his as she pointed toward them. “Power never really goes out,” she whispered.

Malcolm nodded, unable to speak. The sweat on his forehead stung his eyes, or maybe it wasn’t sweat. He watched the girl write, her small hands confident in the dust. The robot sat motionless nearby, but somehow, everything moved.

When the children dispersed for the day, he stayed behind, staring at the chalk words on the wall: Code the Future. The phrase felt less like instruction, more like permission.

As the sun lowered, the generator ticked softly, cooling down. The light turned amber, painting their shadows long across the ground. Malcolm touched the copper bracelet Celeste had given him in the market. It was warm from his skin, alive with pulse.

He thought: This is what connection sounds like when it stops pretending to be signal.

Lottie’s Letter

The email arrived at dawn, its blue glow soft against the dim room. Outside, the Ghanaian morning was unhurried: roosters crowed at odd intervals, a dog barked once and stopped, and the air held that damp, metallic scent that precedes heat. Malcolm sat at the small table by the window, coffee cooling beside his hand, and opened the message whose subject line read simply: A Kind of Goodbye.

Lottie’s words filled the screen, precise as ever, the elegance of a woman who edited her emotions before sending them into the world.

Paris has turned gray again, she wrote. The Seine is swollen, the trees bare, and the city looks like it’s trying to remember its own reflection. Adrien has moved on, as I suspected he would. I’m staying for now—to find myself again, or perhaps to make peace with the version of me that stopped looking.

She mentioned attending a retrospective at the Musée d’Orsay, where she’d seen a Degas painting they once admired together—the ballerinas in rehearsal, not performing but waiting. I finally understood them, Malcolm. All that balance. All that poise. None of it meant for the audience.

Her tone softened near the end.

You once said ambition was a kind of weather—something that passes through us but never belongs to us. I think I understand now. The storm has moved on. I wish you well. Perhaps we were never lost—only walking different maps.

He read the message twice, then again, slower, letting the words expand in the stillness. The light outside turned honey-colored. He felt no anger, only a thinning of something invisible—like breath released after holding it too long.

He closed the laptop. The cursor blinked once, steady, waiting for a reply that would not come. He pressed delete. No hesitation. No archive. Only completion.

He rose and opened the window. The air was thick with charcoal smoke and laughter from the street below. Two boys kicked a punctured football through the dust, their shouts carrying joy like a contagion. He watched them until their noise blended with the rhythm of his pulse.

Celeste appeared in the doorway, barefoot, her hair caught in the new light. She held two tin mugs of coffee, steam curling between them. “You’ve been up early,” she said.

“Couldn’t sleep,” he replied.

She placed one mug before him, her gaze lingering on the closed laptop. “Bad news?”

He shook his head. “No. Old news finally read.”

She studied him for a moment, as if measuring the distance between grief and peace. “Then let’s make new news,” she said, sitting across from him.

Outside, the village stirred awake — vendors calling greetings, radios sputtering to life, the day gathering courage. Malcolm took a sip of coffee. It was bitter, grounding, alive.

He smiled faintly. For the first time in years, the morning wasn’t a meeting to attend or a calendar to obey. It was simply a beginning.

The New Beginning

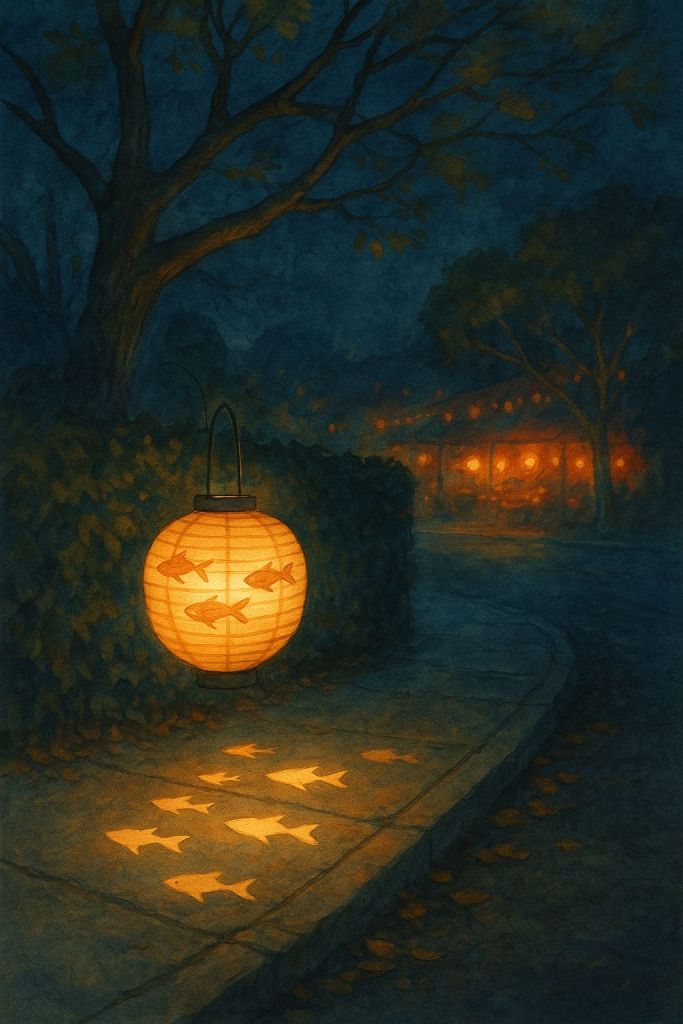

Morning arrived without hurry. It slid over the horizon in slow layers of gold and pearl, turning the palm leaves into silhouettes and the zinc roofs into soft mirrors. On Celeste’s veranda, the air was cool for exactly fifteen minutes — that fragile window before the day remembered it was in the tropics.

Malcolm stood at the small gas burner, coaxing coffee to a rolling hiss. The smell rose rich and dark, cutting through the faint tang of sea salt and charcoal drifting up from the road. Inside, two laptops waited on the table: one open to a dashboard of names and time zones, the other to a cluster of student essays, each title earnest and ambitious.

Celeste sat in a cane chair, one leg tucked beneath her, reading. A pencil rested behind her ear, another between her fingers. The light caught in her hair, drawing a thin halo around the edges. Every so often she underlined a phrase, not because it was perfect, but because it was trying.

“You’re frowning again,” Malcolm said, carrying two mugs to the table.

She looked up. “They keep apologizing for their English,” she replied. “The ideas are better than half the journals I used to review.”

He set the mugs down. “Then maybe that’s the abstract,” he said. “Apologies not required.”

Outside the gate, voices were already gathering — children calling to one another, a motorbike coughing awake, someone laughing at a joke that didn’t need translation. The sounds rose in overlapping layers, the day tuning itself.

They began with the ritual they had built between them. Coffee. A quiet scan of the overnight messages. The inevitable brief skirmish with the internet service. Then the platform came alive.

On Malcolm’s screen, small windows blinked open: Ama’s coding hub down the road, another classroom in Kumasi, a borrowed library room in Nairobi, a modest community center in Recife. Names scrolled by—Adjoa, Rafael, Wanjiru, Lina—and next to them, mentors signing in from Tokyo, Toronto, Oslo, Lagos. Some connections crackled; some loaded in sudden clarity, as if distance had never been invented.

“Room Three is live,” Celeste said, tapping a key. “Oslo and Accra are connected.”

He clicked the icon. A new window opened. On one side, a girl from the village grinned into the camera, her braids bouncing as she adjusted the tablet. On the other, a boy with pale hair and headphones sat in a dim Norwegian winter, the window behind him filled with snow.

“Can you hear each other?” Malcolm asked.

There was a moment of lag, then two overlapping yeses and laughter.

“Today you’re trading stories,” Celeste said. “Not code, not theory. Stories about where you live, what a normal day looks like. After that, you’ll decide what kind of program you want to build together. Agreed?”

The girl nodded vigorously. “We will make one that sings,” she said. “With drums.”

The boy smiled. “And snow,” he added. “We can code snow that listens.”

The audio crackled, stabilized. Their voices grew softer as they began, shy at first, then braver. Malcolm listened not to the words, but to the rhythm — the way curiosity flattened accent, the way laughter sounded the same in both climates.

He muted his microphone and leaned back. “They don’t sound like users,” he said quietly. “They sound like co-authors.”

“That’s the idea,” Celeste replied. “No demos. Just lives.”

Later, under the mango tree near the school, they ate lunch from metal bowls — rice, beans, plantain fried to the edge of caramel. The shade flickered in the heat; the air smelled of sap and spice.

“You know,” she said, “the board in New York still thinks this is a pilot. A nice experiment for the annual report.”

“And what do you think it is?” he asked.

She wiped sauce from her thumb with a corner of bread. “An argument,” she said. “Against the way we’ve been measuring intelligence.”

He smiled. “Who’s supposed to win?”

“Not us,” she said. “Them.”

A lizard skittered across the dirt, pausing to consider their shoes. From the classrooms came the faint clatter of keys, a teacher’s voice rising and falling. The generator coughed, gathered itself, and held steady.

“You listen differently now,” Celeste added, not quite looking at him.

“How did I listen before?” he asked.

“Like a man waiting to rebut,” she said. “Now you wait to understand.”

He let the words settle. They felt less like praise than diagnosis.

In the afternoon, he moved through the rooms with Ama, adjusting a camera angle here, showing a boy how to steady a microphone with a folded cloth, translating an error message into reassurance. He didn’t lecture; he asked questions. When something broke, they fixed it together. When the power flickered off for a moment, groans rose in chorus, then turned into jokes. Someone lit a candle and kept explaining loops and branches with a stick on the board.

He caught himself laughing more than once. Not the polite boardroom laugh, but the unguarded kind that surprised his own chest.

Toward evening, the calls wound down. Screens darkened one by one, leaving dusty fingerprints and faint reflections. The sky shifted to amber, then bruised purple. Children spilled outside, their energy still in surplus.

Someone produced a drum. Someone else clapped a rhythm. There was singing — half a song they all knew, half improvisation. In one corner, two students played back a simple melody generated by a program they’d written, the digital notes oddly shy against the boldness of live percussion.

Celeste stood beside him, arms loosely folded, watching. “You remember what you said in your keynote?” she asked. “About teaching machines to recognize emotion?”

“I’ve tried to forget,” he said.

“You worried they’d recognize it better than we do.”

He nodded once.

“So,” she said. “Do they?”

He considered the question, then shook his head. “No,” he said. “They just notice faster. The difference is what we do after we notice.”

She seemed satisfied with that.

The first call to prayer floated over from a distant mosque, threading through the rhythm of drums. A breeze moved through the yard, lifting dust into a soft veil. The light on the veranda clicked on, more out of habit than necessity.

Celeste turned to him. “So you’re staying?” she asked.

He didn’t rush the answer. The word had already been spoken at the shoreline; now it only needed air.

“Yes,” he said. “To listen first. Then build what matters.”

She smiled, small and genuine, as if he’d solved an equation that had been waiting on the board. “That’s a good order,” she said.

From the doorway of the nearest classroom, a girl waved him over, her tablet held high. “Sir,” she called. “It works! It’s dancing!”

On the screen, a small digital figure moved in time with the drum outside — crude, joyful, a little off-beat, following sound instead of a perfect grid.

He walked toward her, the copper bracelet warm against his wrist. Behind him, the laughter of children mingled with the call to prayer and the hum of the waking night — not a signal, not an algorithm, but a kind of music only present hearts could carry.

For the first time in a very long time, Malcolm Dorsey felt that the bandwidth of his life matched the bandwidth of his heart. And it was enough.